I’ve been making Cheddar today. I don’t intend to make Cheddar professionally – there’s far too much of it about, much of it barely worthy of the name. But living where I do, I’m blessed by being in close proximity to some of the best genuine Cheddar makers, Keens Cheddar (6 miles away) and Montgomery (10 miles away). They’ve been doing it for generations and (not that they’d be the slightest bit bothered), they don’t need me getting in on the act. The world has enough great Cheddars already.

So why am I making it? Well, Cheddar is, perhaps, the archetypal British cheese. A proper West Country Farmhouse Cheddar is certainly one of my Desert Island cheeses and, I think, probably my favourite hard cheese – if I had to limit myself to just one. Of course, Cheddar has become ubiquitous and bastardised: it is made (under that name) all over the world. There are, in point of fact, only about ten genuine Cheddar makers left, all based (naturally) in the West Country. Keens and Montgomery are two of them. If it is not West Country Farmhouse (the official PDO), it is ersatz and simply a hard cheese.

One of the key distinctions of true Cheddar – aside from geography – is the process of cheddaring (yes, it is a legitimate verb). This refers to the technique of cutting and stacking the blocks of drained curd to help expel more whey. The curds are also scalded (heated up) – but this technique is used with other cheeses. The cutting and stacking of the matted curd (the increased weight thus driving out more whey) is intrinsic to the making of a true Cheddar.

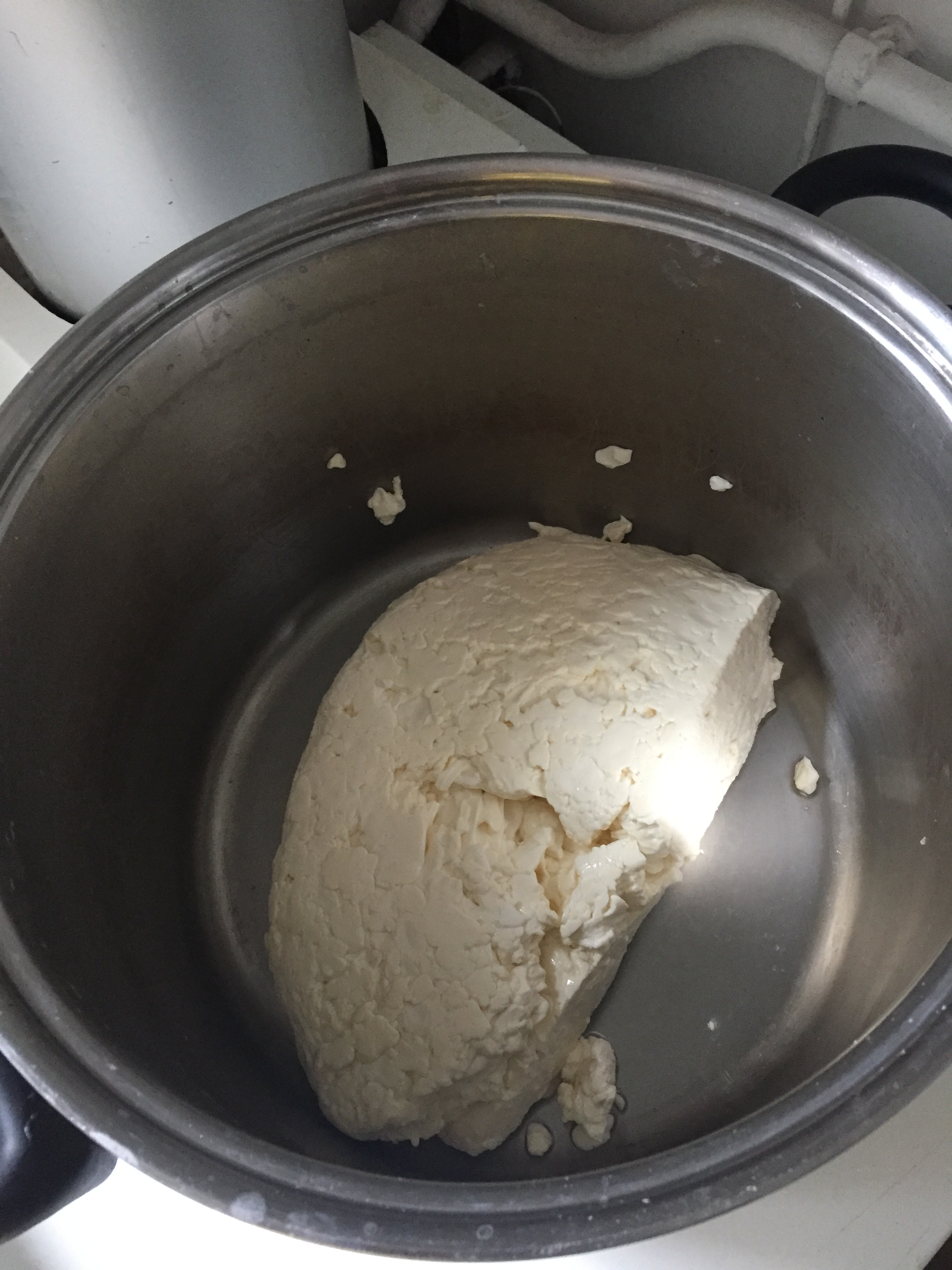

Enough theory. I’m making my own cheddar. The process is largely the same until it comes to the cheddaring. Having cut the curd, I gently heat up the mixture to around 40˚c (remember that up to this point the curd hadn’t – or shouldn’t – have got much above 32˚c). I then stir the curds continuously for fifteen minutes and intermittently for another fifteen. They are then left to settle for half an hour and finally, the whey is drained off.

Hurrah! I’m left with a matted block of curd – which can now be cheddared. Block and stack, block and stack. Turning the blocks every fifteen minutes for one hour.

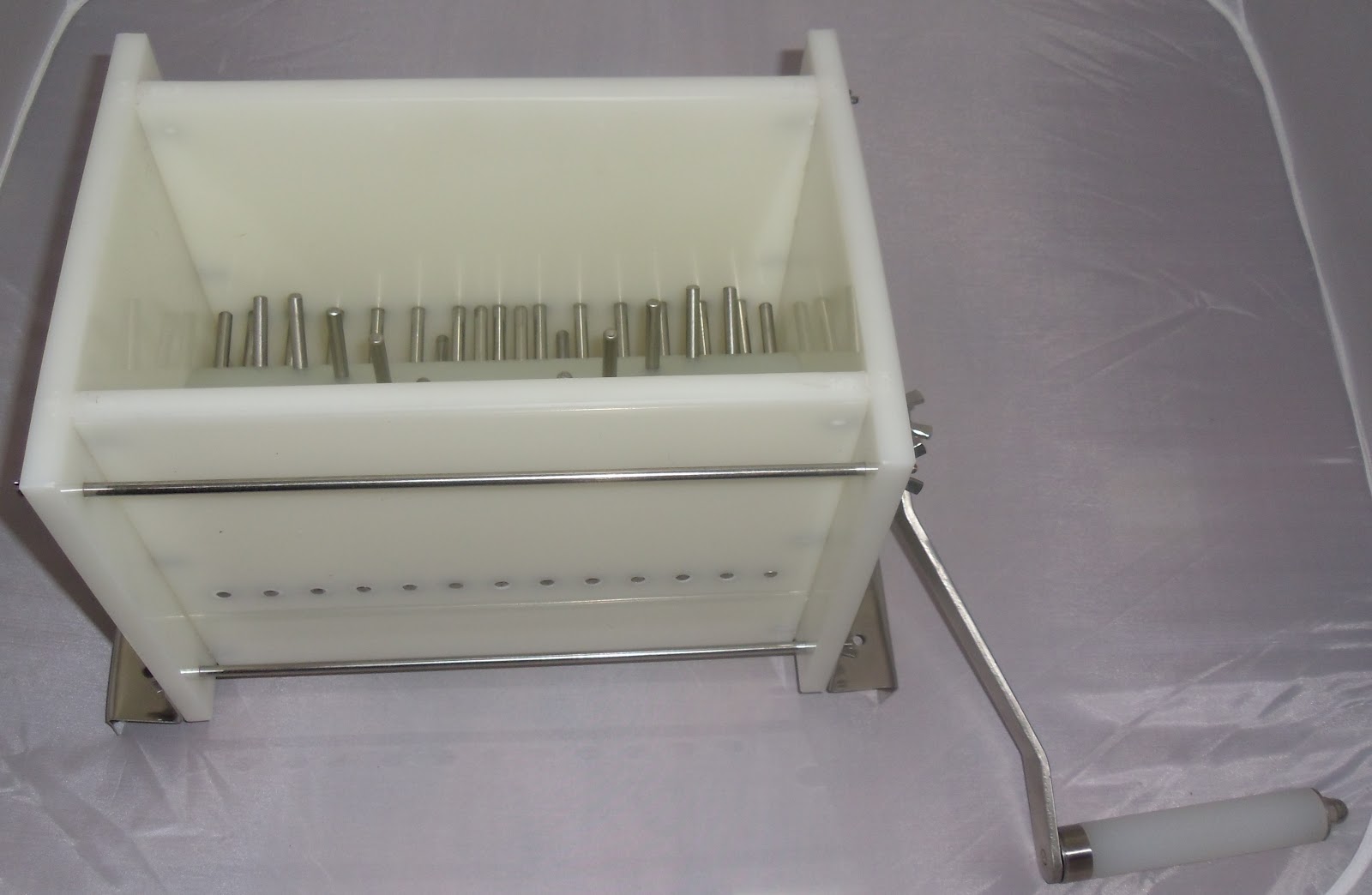

At this point, the curd can now be milled. Professionals will feed blocks of curd into a peg mill – or something even more industrial if they’re at scale.

However, there’s nothing quite like diving in with your hands and breaking up the curd into walnut-sized pieces. The broken pieces of curd are now salted, before putting into the mould and pressed overnight. Pressing again forces out more whey – and ideally you should apply about 4-5 times the weight of the cheese. It’s not an exact science (not for me, anyway) – and a chopping board with a few bags of sugar will do the job. Note the upturned steel cup delicately placed to stop the whole Heath Robinson contraption from collapsing!