I’m going to be a cheesemaker! Penny talked me into it, rather brilliantly.

I’d been scratching my head, wondering how to make a living out of Feltham’s Farm, our 22 acre smallholding in south Somerset. I’d left my job in London in December and although a few head hunters were making positive noises, I knew I was bored of the corporate cut and thrust. I was even offered a role at a big financial PR firm but the very act of offering me a job made me realise I didn’t want it and that I no longer wanted to work in London.

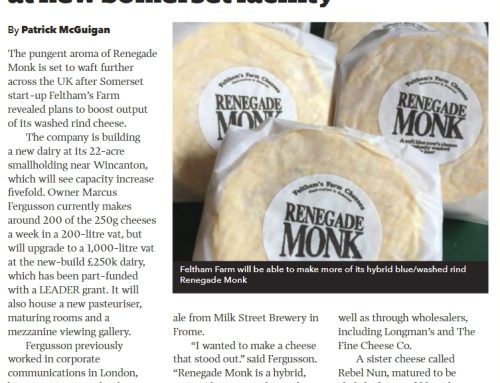

The question was what I could do in the country. Given such a small area of land at Feltham’s Farm, we wouldn’t be able to generate a sufficient income if we tried to grow conventional crops or raise standard livestock. We needed a niche product.

I’d heard that there was good money to be made from garlic but garlic needs well-drained light soil and we live on a marsh with forty foot of heavy clay before you hit the bedrock. There’s a thin covering of top soil but the water table is high and garlic is not going to grow well here.

I also thought about growing wild garlic as it likes the wet – and it can sell at up to £12 per kilo. Wild garlic pesto is a staple at our house in the spring – it keeps surprisingly well in the fridge if you pour a layer of olive oil over it each time you use it. However, wild garlic also likes tree cover and – at least for now – we haven’t got a lot of that. Besides, it’s seasonal so it’s not really a viable plan for the long term.

My next idea was to raise chickens. Not your common or garden table bird but something high end such as the fabled Poulet de Bresse which can retail at around £20 or higher. The Poulet de Bresse has appellation d’origine contrôlée (AOC) status: I would get around this by marketing my chickens as Poulet de b’West (I’m a sucker for a poor pun). But then I encountered some more serious ethical issues. The reason the Poulet de Bresse tastes so good is the way it is raised. Free range for most of its life and fed on a low protein diet to encourage it to forage for insects and grubs. So far, so ethical but they end their days living in an épinette, a darkened cage where they are fed intensively on milk and maize. I figured I could miss out this bit of the process but, in the end, it just made me think that I didn’t really want to be a chicken farmer. I have a cousin who tried it for a bit and she reported that the constant stink of ammonia got a little trying.

Of course, my real passion is cheese but for some reason I was shying away from the notion of making it. It seemed too unrealistic, too fantastical. Instead I pondered over whether I could be a cheese distributor, bringing rare artisanal cheeses from the West Country to a wider, discerning audience. It might have worked. Food distribution is a crowded market but there are still a lot of cheeses out there that are sold in a limited local area.

But then Penny asked “Why don’t you make cheese? If that’s what you care about, then do it.” Again I shied away. Me, make cheese? And then, an epiphany. Why not? It’s worth a go. It’ll be an adventure. Sod it, I thought. I’m going to be a cheesemaker! Thanks, Penny.